Content written + edited by the following contributors: Chloe Linton, Williamson Conservatory Manager; Jason Bonham, VP, Gardens + Natural Resources; Caitlin Conner, Marketing + Communications Manager

Throughout the Conservatory, you’ll encounter many species from dramatically different ecosystems. Desert plants like the Rose of Jericho (Selaginella lepidophylla) and Desert Rose (Adenium obesum) come from arid, rocky landscapes where rainfall is unpredictable. These plants survive by reducing water loss and storing moisture in specialized tissues, allowing them to endure long dry periods. In contrast, understory rainforest plants such as the Shark’s Tooth Orchid Cactus (Epiphyllum chrysocardium) and Rainbow Fern (Selaginella uncinata) are adapted to low light and high humidity, maximizing surface area and light capture while thriving beneath dense forest canopies.

Several species highlight how similar environmental pressures can lead to comparable adaptations in very different regions. The Ponytail Palm (Beaucarnea recurvata) of eastern Mexico and the Desert Rose of Africa both develop swollen bases that act as reservoirs during drought. Tree ferns from Brazil and Australia demonstrate how plants in shaded forests optimize frond structure and surface area to capture limited light, while protective coatings, such as the powdery surface of Odorata Bromeliads, shield leaves from intense sunlight higher in the canopy.

Desert Rose (Adenium obesum)

Rainbow Fern (Selaginella uncinata)

Carnivorous Bromeliad (Brocchinia reduca)

The exhibit also explores unusual plant relationships and behaviors. Carnivorous plants like the Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula), native to the Carolinas, and the Carnivorous Bromeliad (Brocchinia reducta) evolved in nutrient-poor soils where capturing insects became an efficient way to supplement essential minerals. Other plants form partnerships rather than traps. Ant plants, bullhorn acacia and related species provide shelter and food for ant colonies, which in turn defend the plant from herbivores and competing vegetation. These mutualistic relationships have been evolving for more than 140 million years.

Crassula Pyramidalis

Crassula Perfoliata

Buddha's Temple (hybrid cross of Crassula pyramidalis and Crassula perfoliata)

Human influence on plant development is another theme woven throughout Trip to the Tropics. Hybrid plants such as the Buddha Temple Crassula illustrate how selective breeding has been used to emphasize desirable traits, a practice that dates back centuries. Likewise, the Madagascar Dragon Tree (Dracaena marginata) demonstrates how training and pruning can dramatically alter a plant’s natural form, resulting in sculptural specimens that take years to develop.

The history of plant cultivation and transport comes to life through displays on cloches and Wardian cases.

- Cloche – A bell-shaped, glass cover used to protect small plants. Think of it as a mini-greenhouse.

- Wardian Case – A specialized, sealed glass-and-wood container invented by Dr. Nathaniel Ward in the mid 19th Century to effectively transport plants during long sea voyages.

Early bell-shaped cloches allowed gardeners to protect young plants from cold and extend growing seasons, while the invention of the Wardian case during the Industrial Revolution revolutionized global plant exchange. These sealed glass environments increased survival rates on long ocean voyages and reshaped horticulture, trade and botanical science…while also contributing to the spread of invasive species worldwide (which could be a whole other blog post for another day!)

Example of a classic, bell-shaped cloche

Modern example of a Wardin Case

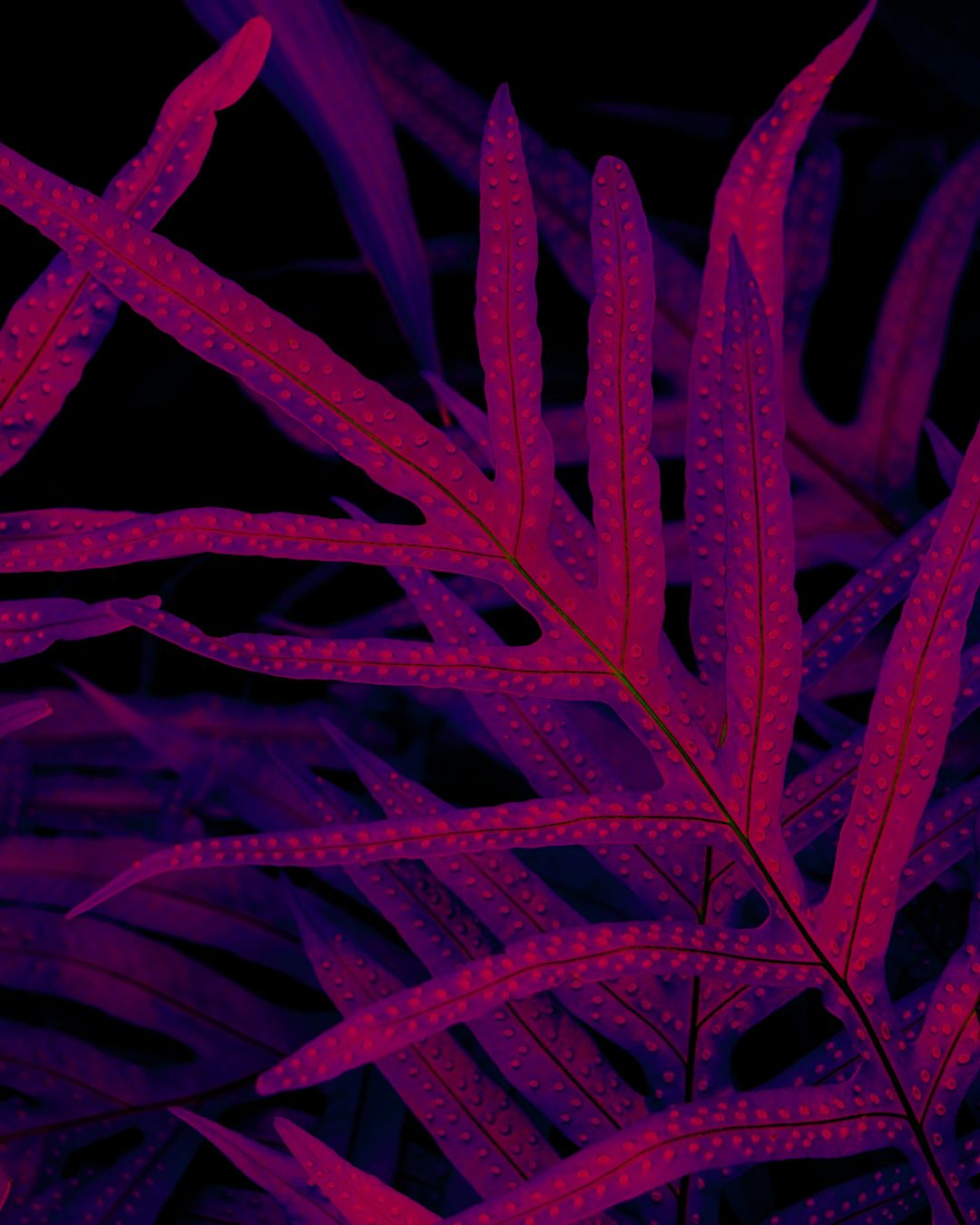

Plant glowing red under UV light

Several sections encourage visitors to see plants in an entirely new way, including displays on blacklight-reactive foliage. Under ultraviolet light, chlorophyll-rich areas glow red, while variegated or non-green tissues reflect blue or white. Floral structures often reveal hidden UV patterns that guide pollinators, offering a glimpse into how insects perceive plants very differently than humans do.

Beneath it all lies the foundation for these mesmerizing plants – soil. A dedicated soil renovation display compares current, new and future soil blends used in the Conservatory, highlighting the balance of aggregates, organic matter, bark and sand required to support healthy root systems. This behind-the-scenes look emphasizes how thoughtful soil management, supported in part by donor contributions, plays a critical role in long-term plant health.

Let’s broaden the story even further by placing individual plants into a much bigger ecological context: one where survival depends on cooperation as much as competition. Central to this story are fungi, among the oldest organisms on Earth. When early plants began moving out of aquatic environments, fungi played a critical role in helping them survive harsh, nutrient-poor soils. That partnership never disappeared; instead, it evolved into what we now recognize as mycorrhizal relationships.

In a mycorrhizal partnership, fungal networks attach to or grow directly into plant roots, extending far beyond the reach of the plant’s own root system. These microscopic filaments dramatically increase the surface area available for absorbing water and nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen, resources that are often difficult for plants to access on their own. In return, the plant supplies the fungi with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis. This exchange is so effective that nearly 80 percent of all plant species on Earth rely on fungi in some form to grow successfully!

We can also tie fungal partnerships to broader themes of adaptation. Just as plants have evolved thickened stems to store water or specialized leaves to capture insects, they have also evolved strategies that depend on cooperation with other organisms. Fungi, ants, pollinators and microbes all become part of a plant’s survival toolkit. By highlighting these connections, the Trip to the Tropics exhibit challenges the idea of plants as passive background elements and instead presents them as active participants in dynamic, interdependent ecosystems.

Together, these stories reveal an essential truth of the plant world: survival is rarely a solo effort. From ancient fungi beneath the soil to the leaves reaching for light above it, plants persist because they are embedded in complex, interconnected networks that have been evolving for hundreds of millions of years…and are still shaping the landscapes we see today!